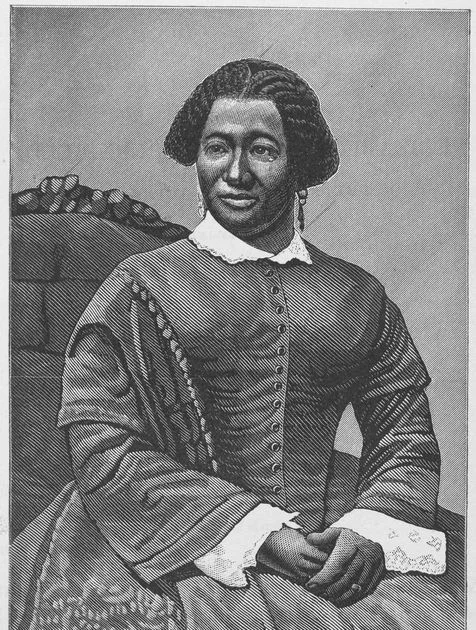

EAR Training FOR HISTORY: Listening to ELIZABETH TAYLOR GREENFIELD'S DOUBLE-VOICED AESTHETICS

FORTHCOMING. THEATRE SURVEY 64.2 (MAY 2023).

The fever pitch of America’s antebellum conflict over slavery coincided with the popularity of the nation’s first Black concert vocalist, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield. With a multi-octave range and a classical instrument, Taylor Greenfield was (in)famous for her convention of singing “white” repertoire in registers heard as alternatingly female and male. This unique performance practice earned Taylor Greenfield the sobriquet of the “double-voiced” singer, since her sonic crossings of race and gender produced perceptual astonishment white audiences could only attribute to more than one body. In “I’m Free,” an 1853 emancipation ballad, Taylor Greenfield dramatized her double-voiced practice to portray both a white male enslaver and a fugitive Black bondswoman.

This essay utilizes the tools of Black feminist performance theory and sound studies to develop a new, performance-based analytic – “ear training for history” -- that attends to voice as a space of theatrical embodiment. The approach gives Taylor Greenfield’s praxis a new, multi-sensorial hearing outside the disciplinary strictures of musicology and refutes historiographies that frame her as Jenny Lind’s mimic. Modeling ear training for history, the essay takes a cue from Taylor-Greenfield and follows a doubled argumentative logic: first going behind the scenes of copycat double-voiced acts in sideshow and minstrelsy to demonstrate how they staged essentialized, one-to-one correspondence between body and voice, then doubling back to the singer’s performance of “I’m Free” to reveal how Taylor Greenfield’s double-voicing unmade the meanings of “Black” and “woman” forged in the middle passage and reified by her copycats. A performance of ear training for history, the essay turns the limited archive of “I’m Free” into evidence of Taylor Greenfield’s singing as a liberatory Black feminist embodied practice.

Nasrid tile, fifteenth century, glazed and painted blue and manganese earthenware with lustre, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, 1948–31. From Bordoy, Guillermo Rosselló. 1992. “The Ceramics of al-Andalus.” In Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain, edited by Jerrilynn D. Dodds, 97–103. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

SOUND ACTS, PART 2: RECEIVING AND REFLECTING VIBRATION

“CO-PRESEN(T/C)ING VIBRATION” BY CAITLIN MARSHALL, PATRICIA HERRERA, MARCI MCMAHON

SPECIAL ISSUE OF PERFORMANCE MATTERS 8.1 (2022): 1-8.

The second of two linked special issues, Sound Acts, Part 2 continues to explore the embodied resonances of vibrational performance as "an improvisational art of living and being with others."

A person listens through Rebecca Belmore’s Wave Sound listening cone at Green Point in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland. Presented as part of LandMarks2017/ Repères2017, June 10–17, 2017. Photo: Kyra Kordoski

SOUND ACTS, PART 1

“CALLING BACK PERFORMANCE STUDIES” BY CAITLIN MARSHALL, PATRICIA HERRERA, MARCI MCMAHON

SPECIAL ISSUE OF PERFORMANCE MATTERS 6.2 (2020): 1-7.

The first of two linked special issues, Sound Acts, Part 1 explores the resonances of sound in the field of performance studies, asking "how the materiality of sound acts as a form of aesthetic and political possibility."

A VOICE LIKE THUNDER: EDWIN FORREST’S SONIC REDFACE

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY 74.3 (2021): 623-32.

On December 15th 1829, Edwin Forrest stepped onstage the Park Theatre to “play Indian” in the title role of Metamora; or, the Last of the Wampanoags. While theater and performance scholars have long paid attention to Forrest’s visible practice of racial masquerade (the actor was costumed from head to toe in skins, feathers, and a thick smear of burnt umber), this essay attunes to what I term Forrest’s sonic redface: that settler colonial speech act wherein Anglo social actors, posing as Indians, appropriate the music and figuration of Native American verbal art.

Commissioned by Forrest himself, Metamora was heavily influenced by the actor’s purported observations of Chief Push-ma-ta-ha and the Choctaw Indians and while on tour of the western territories in 1823. Though Push-ma-ta-ha’s centrality to this authenticating narrative is frequently cited, contemporary scholars have failed to note that Push-ma-ta-ha (d. 1824) was a skilled diplomat, celebrated political figure, and military ally of the US government. He was also a famed orator who appropriated and transformed nationalist American rhetoric to critique Indian Removal discourse and resist US territorial expansion.

In this essay I listen closely to the dramatic text of Metamora alongside transcriptions of indigenous oratory to make a case for Forrest’s sonic redface performance of Push-ma-ta-ha’s verbal art. I argue that Forrest’s sonic redface scrubbed Push-ma-ta-ha’s oratory of its decolonial performativity, refiguring Choctaw sonic sovereignty in service of the settler colonial project of composing whites as “native” Americans. A new avenue for studying white racial formation, sonic redface details how settler colonialism instrumentalizes sound, and draws our ears to the project of decolonizing the American dramatic canon.

Review: “A DIFFERENT VOICE, A DIFFERENT SONG: RECLAIMING COMMUNITY THROUGH THE NATURAL VOICE AND WORLD SONG" by Carolin Bithell.

VOICE. SPECIAL ISSUE TWENTIETH-CENTURY MUSIC 13.1 (MARCH 2016): N.P

CRIPPLED SPEECH

VOICE MATTERS SPECIAL ISSUE POSTMODERN CULTURE 24.3 (MAY 2014): N.P.

QuietBob97 is an alaryngeal speaker who foregrounds prosthetic voices in a series of sound-only YouTube videos. With performances designed to retrain a listener’s ear for different voices, QuietBob aspires to dismantle the stigma of un-naturalness that places the humanness of his voice (and his self) in question. This essay reads QuietBob’s performative moves to develop a theory of crippled speech – the representational crippling of speech and the concomitant desubjectification that attends bodies of vocal difference. Working between crip theory and Foucault’s norm, crippled speech contributes to sound and disability studies a new paradigm for hearing and thinking vocal alterity.

THE ACOUSTICS OF PASSING: HARRIET BEECHER STOWE'S UNCLE TOM'S CABIN AS SUPREMACIST REMIX

SOUNDINGOUT! 23 DECEMBER 2013

At a time when public speaking was out of the question for respectable women, Harriet Beecher Stowe gave her anti-slavery platform a national hearing through her novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Yet Stowe’s novel required a voice that could “speak” in morally efficacious tones against slavery. To stage this voice, one that hinged on a sonic appeal to inter-racial sympathy, Stowe scored a new politically agentive mode of performance, what I term the acoustics of passing. A vocal melodrama (a literal speech act) in black and white, the acoustics of passing spoke felicitously against slavery as a racially "mixed" sonic schema -- one simultaneously reflecting what antebellum America heard as the pathos of black vocality, and the patriotic virtue of white Republican oratory. In this essay, I analyze how Stowe scored this vocal acoustic through her mixed race character, specifically George Harris in the novel's famous passing scene. In a nod to the larger work of the manuscript chapter, I conclude by foreshadowing how Stowe deployed this acoustics to control mixed-race female vocal artists Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Webb.